According to the RIBA Hong Kong Chapter, only 29% of registered architects in Hong Kong were women as of 2017. For this year’s International Women’s Day, which celebrates women's achievements and raises awareness about gender discrimination, we have interviewed women in our school to showcase their talents and experiences as females in the architecture industry.

Prof. Cecilia Chu: Women Should Not Be Hired or Appointed to Committees Merely to Showcase Diversity and Check a Box

Prof. Cecilia Chu, originally from Hong Kong, moved to Canada during her teenage years and later returned to Hong Kong to begin her career as a designer and eventually an academic. From a young age, she was acutely aware of gender inequality in education.

Cecilia shared her early passion in art and design: “I loved creating and designing things, especially furniture. However, my high school in Hong Kong segregated certain subjects of study based on gender. Boys were assigned to the “Design and Technology” (DT) class, while girls were required to take “Domestic Science” (DS). Naturally I wanted to take DT but was unable due to my gender. That was a significant disappointment for me.” The irony, of course, is that she later became a professional designer.

After completing her bachelor’s degree in Canada, she experienced several challenges as a designer in Hong Kong in relation to her gender. One notable challenge involved supervising construction work and communicating with male contractors, who often assumed that women lacked technical knowledge. It took time for her to earn their respect through consistent interactions. A more serious challenge arose in client meetings. Despite being on the same level as her Caucasian male colleagues, clients frequently assumed she was an “assistant” and treated her differently.

Cecilia believes that perspectives of gender equality have improved over time in both the architectural profession and education, but much work remains. "We need more conversations on gender issues. Women should not be hired or appointed to committees merely to showcase diversity and check a box. It is essential to discuss why diversity and equality matter and to raise awareness about women’s empowerment, which can truly benefit society.”

Prof. Inge Goudsmit: We Need More Females in Leading Positions

Prof. Inge Goudsmit shares similar views. “For the lectures we have at our school, I always insist that we need at least half of the speakers to be female,” she said.

Inge’s career spans work as an architect in the Netherlands and China, and now as an assistant professor in academia. She observed that while women now have equal opportunities to enter architecture schools, they still struggle to achieve leadership positions in the industry.

“I remember talking to one of my former bosses that there were fewer women in leading positions in architecture. And he said, well, in our firm that's not the case since we hired exactly 50-50 male and female. And I said, but how many partners are female? And at the time, one out of ten.” she pointed out.

Statistics from a 2014 survey by ACSA (Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture) echo this disparity. In the U.S., 42% of accredited architecture degrees were awarded to women in 2013, yet only 27% of leadership roles in architecture schools were held by women.

“The farther up you look in the world of architecture, the fewer women you see.” the survey concluded. They also pointed out that “the Pritzker Prizes, known as the ‘Nobel Prize of Architecture,’ only 5% of Pritzker Prize recipients have been women.”

Prof. Inge also highlighted the case of Denise Scott Brown, a renowned architect who, together with her husband Robert Venturi helped to spark architecture's Postmodern movement, breaking down the hegemony of modernism which prevailed for much of the 20th century. But when Venturi was awarded the Pritzker Prizes in 1991, Denise Scott Brown was excluded from it. This led to a petition in 2013 for Scott Brown to receive joint recognition with her partner Robert Venturi.

“So, she (Denise Scott Brown) asked, well, we were equal partners. Why did NOT we share that Pritzker Prize? Why was it ONLY given to my husband?” Inge said, “If you ask me whether things have changed. I have to be honest and say ‘No’. It’s been 20 years since I graduated, but I see roughly the same numbers of women in charge. But one thing has changed: the gender issue has been acknowledged for about ten years. Denise Scott Brow did not eventually receive the Pritzker Prize, but at least it started the conversation.”

Balancing work and family has been another challenge. As a mother, Inge admitted, “I've had times that I always felt guilty either at work or at home or both, that I felt like I'm not doing enough. I’m not staying at work long enough. And then I go home, and I feel like I’m not giving enough care.” Despite this, she strives to be a role model for her children, “I hope my children also see that women can work full-time and be successful. And if my daughter asks me, why do you always work so hard? I say because I really love my work. And I think that is an important message to give as well.”

Prof. Maggie Ma: Life and Work Should Be More Integrated Rather Than Separated

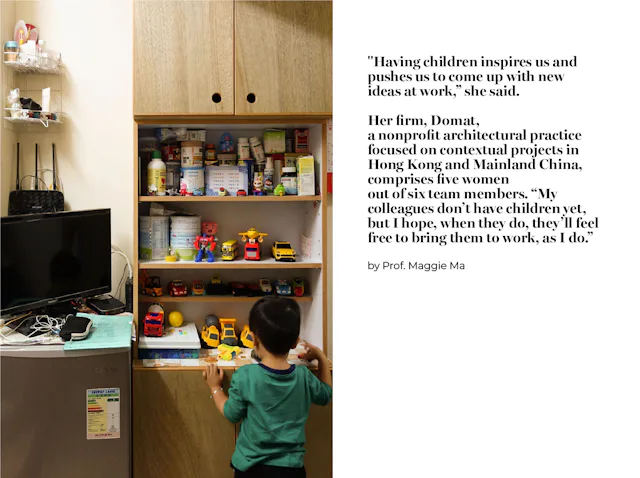

Prof. Maggie Ma tries to handle work-life-balance from a feminism perspective, "I believe that life and work should be more integrated rather than separated. Having children inspires us and pushes us to come up with new ideas at work,” she said. Her firm, Domat, a nonprofit architectural practice focused on contextual projects in Hong Kong and Mainland China, comprises five women out of six team members. “My colleagues don’t have children yet, but I hope, when they do, they’ll feel free to bring them to work, as I do.”

Growing up in a low-income family, she has been inspired to focus on the social projects such as subdivided units (SDU) in Hong Kong. The project “Home Modification for Low-income Family”, for which modular furniture is designed for adaptability and reusability, with sizes that can adjust to various home layouts. Her focus is on each family and their needs. And it was usually the woman of the family who were willing to talk to her and share the challenges they face.

The initiative ensures that SDU residents directly benefit from the improvements, shifting away from traditional approaches that primarily benefit landlords.

She mentioned that she is lucky in that her husband shares the responsibility of taking care for their two children, allowing her to have enough energy to stay active at work, she said, " I think women are strong and capable of doing as much as men—once we’re given equal opportunities."

Joannie Wong: Designing for Empowerment

The idea of gender equality also resonates in the young generations. Joannie Wong, for instance, a MArch student, talked about the same issue with us. She studied gender issues in class and became more aware of them. “I have a brother who also studies Architecture, gets to study abroad with our family resources. Even though I think I’m equally good at academics as my brother, I don’t get the chance to study abroad. That is an example of inequality in real life,” she said.

Focusing on gender issues, she has designed a designated space for women in Nairobi, Kenya, for the Studio of Extreme Conditions. “The challenges women face stem from a lack of accessible resources, leading to severe consequences. In many cases, men are the primary earners, while women are responsible for childcare. Therefore, my intervention involves a lantern resembling a union, attached to the infrastructure of lampposts. It is transformable through user interaction and the activation of space.”

The lampposts, which are easily found on streets and contribute to safety, can be used as sanitary facilities, enclosed changing spaces, trading areas, and workspaces to empower women. “I’m determined to pursue architecture not only in commercial practice but also in social projects that make a real impact,” Joannie said.

Ximena Ocampo Aguilar: Rethinking Public Spaces Through Feminist Lens

Some women in the industry focus on architectural projects that can improve women's situations, while others concentrate on how cities should be built in a more inclusive way.

Ximena Ocampo Aguilar is an architect, city designer, and a current PhD student. She is the co-founder and director of dérive lab, a laboratory based in Mexico that seeks to explore and inspire other ways of living and thinking about life in the city.

Growing up in Mexico, she witnessed many talented female peers leave the field of architecture after having children. “It often feels like a choice between pursuing a career or becoming a stay-at-home mom. But we shouldn’t have to make that choice. There should be more support, such as maternity leave and daycare, so women can have equal opportunities. And we should also be thinking of other more collective systems of care, that can also contemplate our wellbeing.” she said.

Her project ‘[otras] maneras de ocupar el espacio público’ ([Other] Ways of Occupying Public Space) explores how people inhabit the city.

“I pay attention to the ubiquitous everyday activities, like a parent changing a baby’s diaper, or people sitting on almost anything in order to rest, eat, talk.” she mentioned, “I think that’s something that feminism has given to us as well. You have to pay attention to how people, especially women, children, and the senior adults use space and what are their specific needs. When cities were planned, they were usually designed by male architects and decision-makers who may overlook the needs of such social groups. So I find this feminist lens really crucial for understanding cities today.”

Prof. Melody Yiu: Bring Awareness to Gender Issues Through Creative Designs

Prof. Melody Yiu’s journey into architecture began with her love for design and art. Her parents, however, discouraged her from pursuing art. “They told me, ‘Don’t be a starving artist!’ So, architecture seemed like a logical choice,” she joked.

Studying architecture opened up her interest in ‘how cities are built’ beyond a particular building, leading to her practice in urban design for 10 years before turning into an academic career.

Alongside her research in architecture and urbanism, she joined Atelier In, an architectural collaborative that aims to raise awareness of gender issues in everyday living through research and creative design initiatives. She partnered with the founder, Veera Fung, an architectural designer and Research Associate at the School of Architecture, CUHK, on various projects.

One of their projects, The Curiosity Cabinet of Gendered Objects, reflects how gender identity operates in domestic spaces. “We started by collecting everyday items we found at home and displaying them as an exhibition inviting participation. Visitors would come in and be given a sticker indicating the spectrum from masculine to feminine. And then they would put a sticker on the particular object.”

The colourful stickers on the items illustrate how people perceive these domestic items in terms of gender. “We noticed stereotypes—like aprons being seen as feminine—but it’s a creative way to reflect on these biases,” Melody said.

As we reflect on the insights shared by these remarkable women in architecture, it becomes clear that their voices are not just advocating for change; they are paving the way for a more inclusive future in the industry. The challenges they face highlight the systemic barriers that still exist, but their resilience and innovative approaches demonstrate the power in addressing gender issues.

By fostering open conversations, challenging stereotypes, and promoting equal opportunities, we can create environments that empower all individuals—regardless of gender.